By the term seed system, we refer to the activities, institutions, and actors involved in the development, distribution, and use of seed and other planting material.

The prevailing seed systems in Africa can be broadly categorized into three groups as informal, formal and integrated seed supply systems.

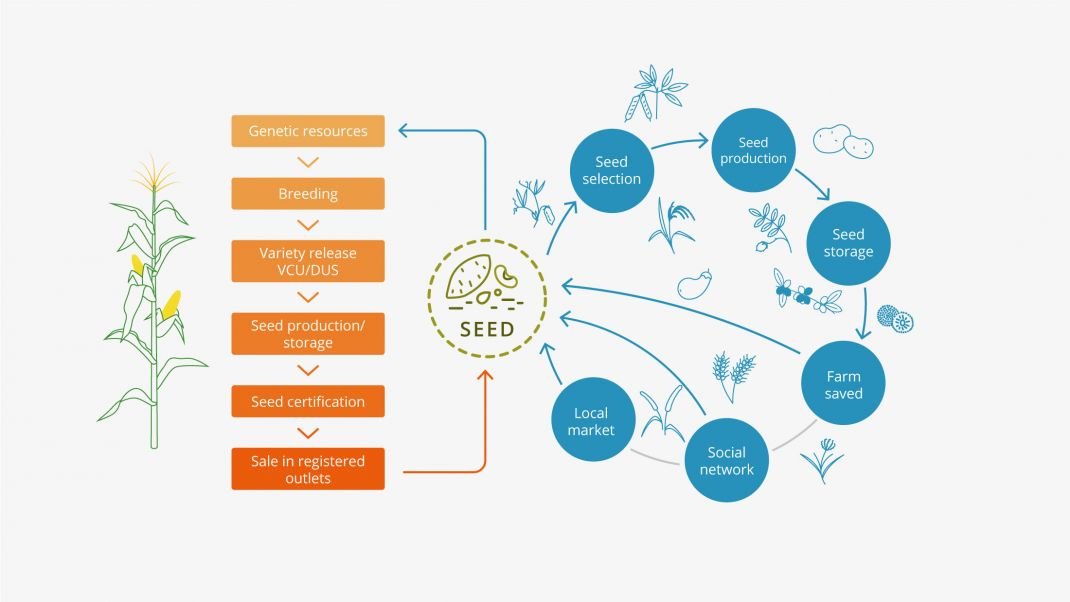

The fact that there is a lot of seed- and gene-flow between the formal and the informal seed system has led some authors to suggest that a better term to use is farmers’ seed systems. The relative contribution of each seed system to the national seed supply differs between the InnovAfrica case countries, however farmers’ systems deliver the bulk of the seeds used for most crops in most countries in SSA. In informal seed systems there is no seed certification involved in seed production, and distribution processes are not monitored or controlled by government policies and regulations but rather by local standards, social structures, and norms. The formal seed system is the chain of activities and institutions involved in the breeding and dissemination of certified seeds of improved varieties. Thus at the base of the formal system is the science of plant breeding, in either public organizations or private companies. In all six InnovAfrica case countries the formal seed supply system has been operational for years and the private sectors are also involved at different levels. The strongest involvement of the private sector is found in profitable seed markets such as hybrid maize, vegetable seed and other crops of high commercial value. However, the reach of the formal system remains limited for most crops in most of the InnovAfrica countries and the integrated approach to seed system development has a potential to harness the strengths of both informal and formal seed systems.

Integrated Seed Delivery Systems (ISDS) are also called ‘intermediate seed sector development’, specifically denoting approaches such as community-based seed production and community seedbanks (CSBs). Activities and institutions in this intermediate sector may work at one or several stages in the seed value chain, inter-alia: Participatory plant breeding or variety maintenance at the variety development stage; Participatory varietal selection at the evaluation stage; community based seed production (by single farmers, farmer groups or cooperatives) at the production stage; alternatives to seed certification as quality approval such as ‘Quality Declared Seed’ (QDS), ‘truthfully-labelled’, and ‘farmer-guaranteed seed’ categories.

InnovAfrica has introduced, tested and analyzed these approaches in Ethiopia, Malawi, and Tanzania.

In Ethiopia, InnovAfrica has worked closely together with the ISSD Ethiopia program through the shared partner Haramaya University and the seeds used in the SAI Farmer-led field experiments on Maize/Millet - Legume cropping system are sourced from the integrated seed system existing in the site. In Tanzania, farmer seed producer groups were engaged in seed production and QDS seed production in close collaboration with the local branch of the agricultural research station of the national research organization and certification organization. In Malawi, seed and variety selection has been a central issue in the implementation of the EAS Farmer Participatory Research / Farmer to Farmer Extension (FPR+F2FE) which has been integrated with the Farmer-led field experiments on Maize/Millet - Legume cropping system SAI in the country. Furthermore, the principle of harnessing the local seed system through participatory varietal selection and farmer to farmer extension is fundamental for the Brachiaria forage grass testing and upscaling in Rwanda, Kenya and Tanzania. At the policy level, the MAPs have been involved in discussions, giving feedback and dissemination of the concept of integrated seed delivery systems. Thus, ISDS, has been mainstreamed across the innovation levels in InnovAfrica. Currently InnovAfrica team members are part of efforts to put farmers’ seed systems and seed security on the agenda of the UN Food System Summit that will be held in New York in October 2021.

Resources:

InnovAfrica Technical Brief on ISDS (2018)

InnovAfrica Journal article about seed system governance (2019)

InnovAfrica report from pilot study on upscaling QDS production in Lindi, Tanzania (2020)

Figure 1: Linkages between formal and informal seed systems. The blue circle frames the informal system and the arrows indicates seed and gene flow between the systems. Source: After Louwaars and de Boef (2012)

Figure 1: Linkages between formal and informal seed systems. The blue circle frames the informal system and the arrows indicates seed and gene flow between the systems. Source: After Louwaars and de Boef (2012)